Whitbeck Notes

Spring 2020

There is much more to a painting then what you see right away, much more to the images in a museum as you pass along from one painting to another. It is easy, even understandable, to miss all els that might be hidden away beneath the layers of paint and years of dust, dirt and soot. Almost a whole other painting! Just think of all the stories that wait there, looking you right in the face, wondering if you will notice them. Wondering if you will catch something, and curiosity piqued, look a little deeper. What I am talking about is the materials, the busy studios, the ships and the caravans, the grand palaces and the dark alley ways, the faces and the conversations. There are so many stories here just waiting to be told! Take, for example, Saint Sebastian, standing before you on the gallery wall. There is a story in this. He is no Sebastian, and probably not much of a saint, but he has a story. Just outside of the artists studio, a bit down the cobbled street and at the second alley on the left is where you will find him. He is a beggar, he does odd jobs about the city and once in a while you can find him at the Westerkerk where he takes advantage of the churches generosity and accepts the second hand clothing that is handed out there as well as food. He has strength in his arms and shoulders from the heavy labor he does down at the warf and so physically he will fit perfectly as the model for the artist. He is the man in the huge canvas you see before you, stuck with arrows and looking all saintly. Our artist, as well as many other artists who are in the habit, have payed this beggar a few stuivers to sit for him when he is in the need of a figure for his history paintings.

Another story could come from the fine, gleaming white sugar mounded up in the little silver bowl, sitting all arranged with the other opulent objects in that very fine still life in Amsterdam's Rijksmuseum. What a horrific story of forced labor that one is! Like now, most times we do not realize just in what manner something, some everyday object has made its way into our homes. But most likely they knew, way back in 1690. They knew of the blood, of the sweat, of all the tears that had went into the production of this ever so delightful sweetener that is stirred into the latest beverage craze called tea. One nation enslaving another for the perfection of profit and not finding any moral wrong doing in it. This is how the world works in their minds and there is nothing strange about it. They live in a "civilized" country. This is a story.

Now let us even take a look at the canvas itself, turning the painting around and observing the linen support. Such an overlooked thing for most. But dive in a bit and you get the whole history of the cloth guilds going all the way back to early medieval Flanders. The Fullers Guild, the Weavers Guild, the Dyers Guild and of course the famous Van Ardeveld's of Ghent and their popular rebellion against the Count. There are so many stories hidden away in the threads of this weave!

But what I want to talk about today in these Spring Whitbeck Notes has to do with the magnificence of a certain color, a color thats story reaches far across oceans and lands, finding contact with people from many different nations and religions. A remarkable story really, and one that is worth laying out for you here.

White dust, bloody knuckles. The only light is from a tallow lamp that has been spiked into the tunnel wall, illuminating the stone passage that pushes on into the darkness. Since early morning, before the sun came up he has been chipping away where the thin blue vein had been. This vein giving hope that the "blue treasure" is buried somewhere in this part of the vast mountain range. His hennad fingers, tough as boiled leather, smartley grip the spike while his other hand holds the mallet that strikes away on the spikes blunted end. Deftly, with an unconscious effort acquired after many winters spent inside the mountain, he works away, small chunks, large chunks, falling away to the floor then dragged away on a sack and dumped out the cave entrance down the mountain side.

There are three other men from his village here too. Over time it was discovered that a scarf wrapped around the face would help with the dust, that ever present dust. White, fine and powdery. Out of your mouth it might stay, but not out of your eyes. There was nothing you could do about that. So at the end of the day, drinking tea down in the mining town, all of those with you would be red-eyed. They have been here for a few months now and have not had much success. Our man will stay another two months. He needs the money that he can get from this precious blue stone. Hoping that this vein will lead to a large deposit, he keeps working away, they all do. The symphonie of tapping mallets on spikes, hour after hour does seem like some sort of agreement: tap, tap, TAP, tap, tap, TAP, tap, tap, TAP ...

What they are looking for is Lapis Lazuli, a metamorphic rock that has been prized since antiquity, a rock that is comprised of a mixture of minerals with it's main constituent being lazurite. They do not know this, nor do they know the vast amount of money that is payed for these rocks after leaving their hands, but they do know that what is earned from even a few pieces of this lapis lazuli is enough to keep their families fed for quite some time.

The area they are working in has been mined for as long as they can remember and as long as their fathers and grandfathers can remember. This is the Sar-e-Sang valley of the Badakhshan Province in what is now northeast Afghanistan, high up in the mountains, days away from the nearest village and reached only by steep mountain passes. At days end they bypass the winding trail that heads back to the mining village and just head straight down the mountains side, feet sinking into the crushed stone that they have been emptying from their months of chipping away in the tunnels.

The mining village is a small cluster of low windowless huts. This is where they gather to eat, drink tea and rest at the end of a long day. There are no women here and no other family save brothers, fathers, cousins. This is their home for now, their place to be until they have collected enough of the precious stone, at which point they will sell it to the man from the caravan who will haul it away on his ponies.

The sun comes up and back to the mines they go, following the switch-back trails up the side of the mountain. The entrance to the mine gapes open on the mountains face, about 1,500 feet above the stream that lies below. At the entrance flint and steel is produced and struck together, showering sparks onto a small black piece of charcloth which catches and begins to burn. Put into dried grasses there is smoke and then a burst of flame, from which the torches are quickly lit. They enter the shaft, carefully making their way along, sometimes having to crawl on knees and hands at points where the roof has fallen in. Some sections of the shaft have names, given by friends of those who have been killed by the collapsing of a roof. They continue on. One of them is carrying along dead branches collected from the evergreen shrubs that grow down by the river. This is crucial material for extracting the blue stone. Sitting down at a promising spot in the shaft he starts a fire with one of the torches, igniting the branches that have been piled up at the base of the wall. They watch as the flames start to flicker over the rock surface. The chill cold inside the mountain passage fights against the flames and it takes a while before the white stone surface is sufficiently warmed and the chipping can begin. Soft conversation floats throughout the tunnels as they wait. With chisel and mallet the flakes begin to fall and pile up on the floor, another man scrapes them up with a wooden shovel, pushing them onto a large sheet to be later dragged out and dumped down the mountainside. With success Lapis Lazuli will be found, at which point a groove is chipped out around the stone and a flattened metal bar is inserted to pry it out of its home. The fire softened stone makes this job easier, and as the encasing stone falls away, the real treasure becomes more available.

Meeli, Asmani, and Suvsi. Our man hopes for the first one, but has come across the second, light blue in color and worth less but will still bring some money. Meeli is more indigo in color and is the most desired, and Suvsi is collected if found, but not the one these miners are hoping for.

His brother-in-law works on the opposite wall while his nephew, big enough to haul the blanket of shards out of the shaft and maintain the fires, now keeps watch over the small pile of various sized Lazuli that they have so far collected. The blue stones sit in contrast to the white of the tunnel walls. They stand out in the environment of this land, the land that this family has grown up in. These stones have been so many thousands of years hidden away inside this vast mountain range. Now the blue comes out of the mines, into the thin air, hauled by these men into the red and brown of their world with the only comparable color being that of the clear blue sky.

The following day they will pack up their stones at the mining village and head back down the network of mountain trails into the village that has been, as long as anyone can remember, the place where the "blue treasure" is sold and carried off by small caravans to the large cities. Dusty rough hands carefully wrap each piece of Lapis Lazuli in scraps of cloth, and these in turn are then placed in the woven saddle bags that hang on each side of the waiting ponies, about ten all together. With safety in numbers, most of the men from the mine will depart together. It is easy enough to take stones from one lone man traveling in the deep mountain passes. A flintlock musket, knives or clubs would do the trick. But a large group moving together would give second thought to would-be bandits. Others stay on in the village, chipping away in the tunnels hoping for their successful vein to lead them to good quality lazuli.

These villagers know that the stone is valuable and that its rich color is what makes it so, but once it leaves their hands and is carried away, buried in the vast caravan of camels and ponies, headed to the large city of Herat, after this they know nothing of its journey. And, really, it does not matter. They have found their stones, chipped them out of the mountain and sold them, making enough money to take care of their families and carry on as they have always done. Watching the animals kicking up dust as the merchants make their way out of the village, our man turns and goes to ready himself for his own departure, back to his own village and family.

Now our precious ocean blue stone starts off on its second leg of the journey, heading ever West through the mountain passes, in and out of snow topped peaks, along flowing rivers, eventually to emerge into the wide plains and then, months later to hit the "sea between the lands", the great Mediterranean. Here, in magnificent cities built along the shores our stones would now hear words from various languages like "prendi questo" or "afto einai vary" or even "eshte shume e nxehte". The rugged interior hinterlands of the east will now give way to the salty breezes of the Mediterranean coast, the slow but steady stride of the dromedary and pony will be replaced by the seemingly endless rolling and bobbing of a merchant ship and then, eventually, our stone will end up being bought by a painter in a little apothecary shop situated along a muddy, wagon rutted street in a city of the great Dutch Republic. But all of that will have to wait for some future Whitbeck Notes.

_______________________________

Vibrant Floral

18" x 14" oil on panel

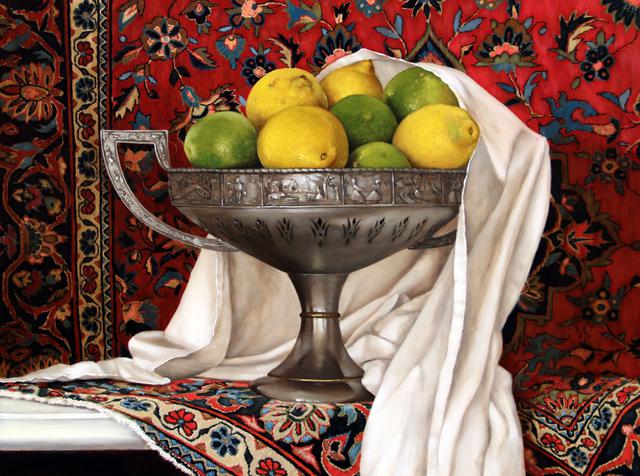

Kashan and Fruit

18" x 24" oil on panel

Dallah with Coffee Beans

14" x 18" oil on panel

Spring is right around the corner as is the 2020 art show season, so be sure to take a look at the

Art Shows page of my website to see the latest updated list. Also, visit the Paintings page to view all new paintings coming out of Whitbeck Studios, with more to come before I hit the road in June! I hope you have enjoyed these latest Whitbeck Notes, and I look forward to seeing you all this year.

All my best,

James Whitbeck

(413)-695-3937

__________________________________________